One of the biggest goals I have when I teach poetry is the restoration of the creative birthright, the idea that we all can be and in fact already are poets, writers, artists.

I love watching people’s eyes light up, their shoulders relax, their pens start to move, their backs straighten as they watch themselves write, then maybe even share what they have just composed on the spot. Creativity is our birthright; it is the force that keeps the world growing, changing, inventing, renewing. It is there in us even when it gets warped, suppressed, expressed in thwarted or unhealthy, even destructive ways. (Arthur Mindell says in his book The Shaman’s Body: When a people fail to dream, we dream in guns.) Thwarted creativity is actually destructive.

So, my personal mission has been to help anyone I meet in a workshop or writing retreat to re-acquaint themselves with their creative inner child, the one who for whatever reason grew up to believe she was not an artist, who was either told she was no good or who told herself she was no good. Or perhaps the world told her there is no place for her art, at least not within the framework of a successful, responsible life. I have seen so many people realize that they do in fact have the healing flow of words within them, just below the surface, and I have seen the power of those words to change both their own hearts and the hearts of those with whom the poems are shared.

If anyone is familiar with Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way, you know the power of morning pages, artist dates, and the simple daily practice of leaning into our trust in our own creative selves.

I’ve been preaching this sermon for a while now. And, yet.

This weekend, I went to an absolutely incredible “Healing Sound” Drumming & Chanting retreat with my husband at the Shambala Mountain Center in Red Feather Lakes, Colorado, led by the amazing teachers Christine Stevens (UpBeat Drum Circles) and Jonathan Crowder (Peak Rhythms). The retreat was a powerful time of community, rhythm, prayer, healing, and devotion. We sang, we danced, we drummed, we rattled, and we carried our offerings of sound and love in the culminating procession to the beautiful Stupa of Dharmakaya, where we laid down our instruments and took up our own most primary instruments: our voices. We chanted in the kirtan style, invoking many languages and sacred songs from across traditions. We cried. We swayed. We laughed. We shouted with joy. We pulled others who had joined us into our circle and THEY dang and cried and swayed. We sent our most heartfelt prayers for the world straight up and out of that Stupa, straight up to the jewel-bright stars. It was a night to remember. And for me, it was life-changing.

Despite all my talk about our creative birthright and the ability we all have to be poets and artists, I have been leaving out an important word. Somewhere along the line I had convinced myself that I am not musical.

I have been believing for so long now that I missed the boat for music, that I just didn’t get the singing voice and that I should have kept up with the piano lessons from the 5th grade but didn’t, so now it’s too late. I have harbored pipe dreams of learning the guitar or ukulele, but those dreams kept the possibility of music at arms length, and at best several years away from whenever I decided to do something about it.

I have been longing to bring music into my chaplaincy practice, to bring melodies that bring peace, joy, remembrance to my dying patients.

Except for the times when I am desperate and compelled to sing to them, I have had to outsource this desire, playing music on my phone or asking outside groups to bring the music in. (And, sometimes they don’t get there in time.) Strangely and by grace, my singing is better in this setting. I have surprised myself with the most heartfelt renditions of Amazing Grace. Hymns have come out of me that I never knew I knew (and have since forgotten). Once I taught a daughter a Spanish Taize song to sing at the bedside of her dying mother. So, somehow, I have been doing this all along. And yet, in a big way still, I have been denying myself, and my patients, the music in me. The truth is, I thought there was no other way. I mean, how quickly could I possibly learn the guitar? And forget learning music theory or even reading music—that too ended when I stopped piano at the age of ten.

This weekend, with my loving group and encouraging, playful teachers, I realized: this is so much easier than I have been telling myself it has to be.

I have been putting up so many barriers to my own creativity, to the music that wants to come into my life and through my life. Sure, great music takes practice; great music takes years of experience. But GOOD music can happen any time, around a fire, with just a drum, a rattle, a chant, the basic beat we all have inside, and a willingness to go for it. The beauty of chanting, and drumming in a group, is that there’s no pressure on any one person. This isn’t a performance. It’s more about harmony and rhythm than accuracy or pitch— a very lucky thing for me. Still, every voice counts, every instrument adds to the whole and would be missed if it were absent. And we had some good, good music this weekend.

During our last session on Sunday morning, our endlessly generous teachers invited me to read a poem I had written the day before, and we as a group put it to music. I don’t mean we wrote a score; we improvised on the spot. We chanted the lines in rounds. We took words and ran with them. We got up and we danced.

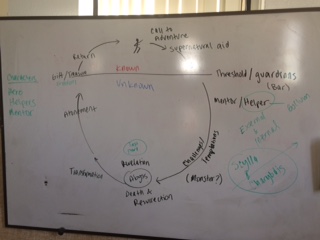

Never have my words been honored in this way, and quite soon they were not my words at all; they were the group’s words, lifted and carried and given new life. I’m finally understanding something I’ve known for a while to be true: music is the original home of poetry. It felt so right, and it felt so freeing. The poem didn’t have to be this tight-knit thing because each part of it had a life of its own that could take off running, or dancing. I still love a good, well-crafted poem; that kind of poem has its own, quiet kind of music, its own form of harmonic resolution. But for the first time in my life I think I’m understanding what it is to offer my words up to the fire, to watch them become more than my own, to watch them dance, and to watch them fade. Who cares if they get written down? And that’s in part why, originally, they never were. Songs and stories were passed down through generations, and they were allowed to change with every telling, every singing. They were alive. They transformed.

We create, as we live, in the present moment. Perhaps that Stupa had more power over me than I realized: I am feeling less need to hold onto things, to call them mine. To hoard as if there might not be more where that came from. Annie Dillard says in he beautiful book The Writing Life:

“One of the things I know about writing is this: spend it all, shoot it, play it, lose it, all, right away, every time. Do not hoard what seems good for a later place in the book or for another book; give it, give it all, give it now. The impulse to save something good for a better place later is the signal to spend it now. Something more will arise for later, something better. These things fill from behind, from beneath, like well water. Similarly, the impulse to keep to yourself what you have learned is not only shameful, it is destructive. Anything you do not give freely and abundantly becomes lost to you. You open your safe and find ashes.”

I cannot tell you how excited I am to start bringing music into my life, to start letting it flow through my life. It was as though a huge part of the human experience had been waiting for me behind a door I had locked and told myself was not for me. I had forgotten I had the key all along. Thank you, Christine and John and my beautiful tribe of musicians, for showing me where I had put it.

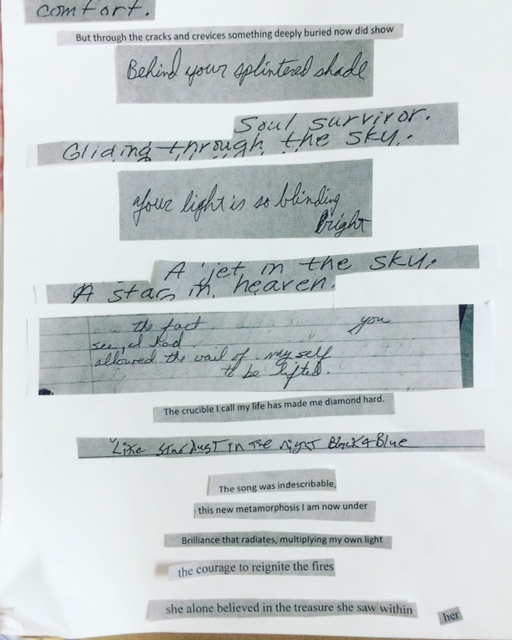

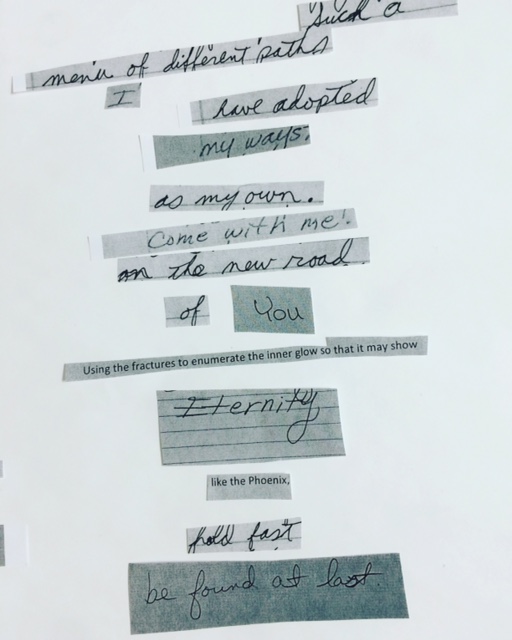

Here is the poem we chanted on Sunday morning:

THE HEART KNOWS WHAT IT KNOWS

Originated at the 2019 Healing Sounds Retreat

Shambala Mountain Center

The heart knows what it knows

and the mind will catch up later.

Science finally dances

at the edges of our fire.

Let us let in all the skeptics,

our own hearts first.

Let us welcome them

with the drumbeat.

Let us cry loudly

to those who least believe:

you are home. Home. Home.

The heart knows the tune.

The mind, if we are lucky,

names the dance.

Here comes the dance!

You can’t help it.

Ah, what a chill.

Ah, what a wind.*

*Borrowed from the end of a Peruvian Dance song by the Ayacucho Indians (Source: Technicians of the Sacred p. 90)

And here is me, with the Native American flute that I took home with me, thanks to Christine and High Spirit Flutes. I cannot wait to play. And I do mean, PLAY.